It’s that time of year when I refuse to play golf—the season when the earth tilts away from the sun and the light grows shallow and uncooperative. Cold settles in. The days feel narrower. Gloom has a way of provoking thought.

One observation, for what it’s worth: the deeper I journey through life, the less I want to work.

Let me clarify.

The less I want to work for money.

That doesn’t mean I’m giving away houses instead of selling them. It means something else entirely. It means I’ve come to believe that work has intrinsic meaning—an embedded code in our creative nature that urges us to sing, write, play the piano, paint, photograph, bake bread. It means we live for something deeper than what can be measured in the shallows of financial worth.

I’m writing a book about a town that once had twelve thousand residents, just a few miles from where my dad was raised. My grandmother always referred to herself as a coal miner’s daughter. I’m convinced Loretta Lynn borrowed that line from Grandma Taylor.

The town is gone now. Only ghosts remain—empty houses, poisoned streams, a ruined landscape.

The work done there was brutal. Digging shafts. Coring holes. Setting dynamite. Crushing muck into ore. Loading railcars bound for smelters that turned lead and zinc into bullets and armor. Perhaps half the bullets fired by Americans in the two world wars came from those mines, along with the armored plating for tanks, planes, and ships.

I have no idea how anyone endured such dangerous labor for so long. Many didn’t. Some worked those mines their entire lives and died far too young.

There was a time when people spent their whole career at one place—Phillips Petroleum, for instance—and retired with a gold watch. Today, people change careers the way they change shirts. And yet, in some ways, that’s a gift.

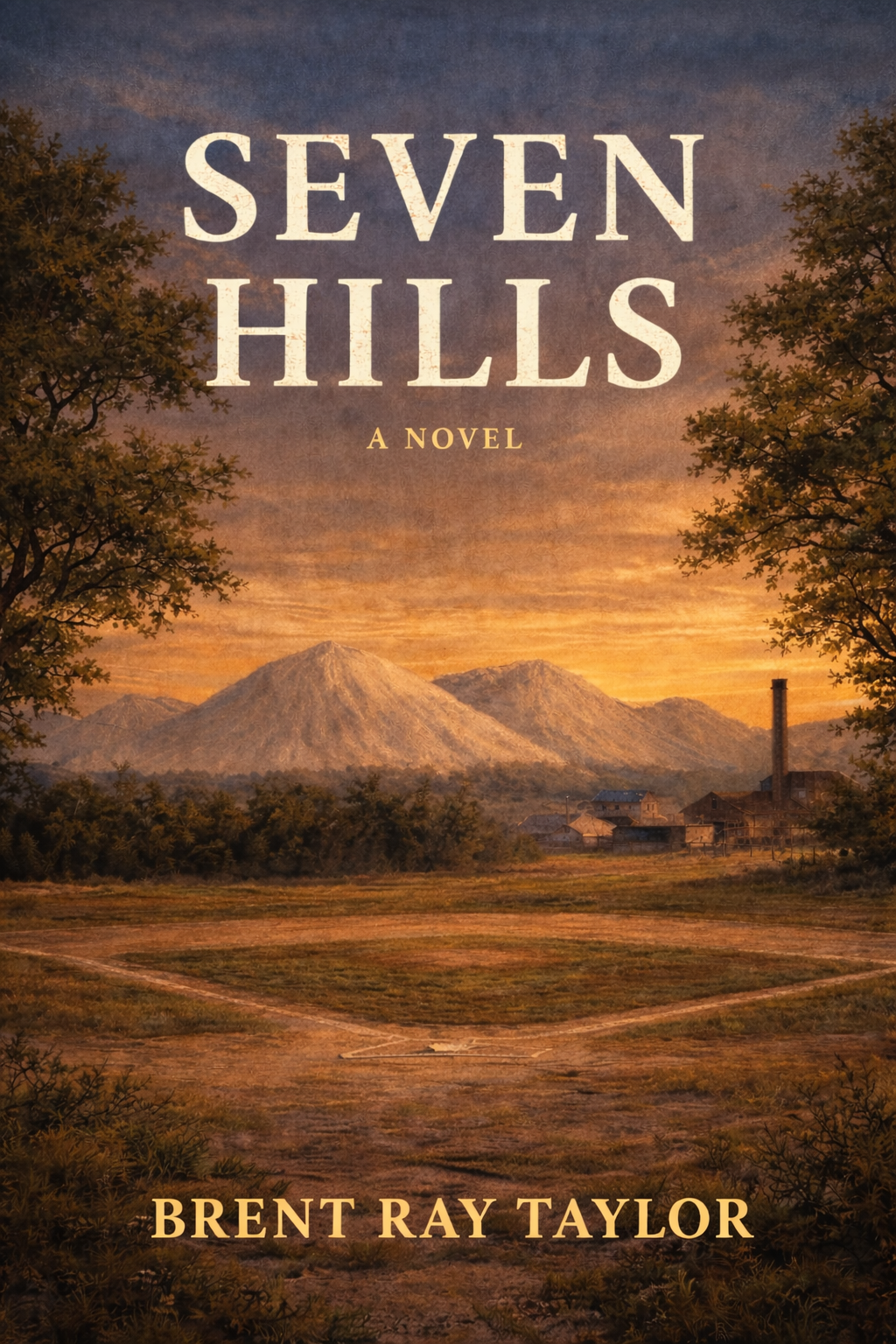

I’m writing a novel called Seven Hills.

My daughter is baking and selling bread. (see Facebook: Bread on Brookside) It’s delicious!

My brother runs a wood shop, reclaiming discarded lumber from job sites and turning it into wooden blocks for children. North Wood Toys

We haven’t forsaken our day jobs. The point is that we now have choices—opportunity, creative canvas, and technology that makes the world more efficient and more open than ever before.

If you bump into me on a plane and have no idea who I am, I won’t tell you I’m a real estate developer, a home builder, or a retired CPA. I’ll tell you I write for a living: a blog, articles for Bartlesville Monthly, a novel called Seven Hills.

We write.

We bake bread.

We make wooden blocks.

We do these things because we hear the whisper.

The whisper doesn’t come from hunger pangs or mortgage payments. It comes from somewhere deeper—places you only discover when you slow down long enough to listen. Like Elijah at the mouth of the cave, who didn’t hear God in the wind, the earthquake, or the fire—but in the still, small voice.

In one section of my book, a character says to another, Look around.

“While you still had breath, you told me to look around.

You said, ‘It’s beautiful, isn’t it?’

And I said, ‘What?’

And you said, ‘All of it.

Your smile.

Sailboats in September.

The first pitch of spring.

Horny toads.

Frenetic squirrels burying nuts.

The optimism of dogs chasing cars.

An inside-the-park home run.

A woodpecker at work.

A goldfinch singing.

People laughing so hard they can’t stop.’”

I’m guilty. Guilty of working so hard that I forget to look around.

Spring is coming—but don’t wait for the buds to break through.

Draw a picture.

Talk to a child.

Play some music.

Create something beautiful.

There is still time.

You don’t have to change careers.

Just look around. It might change the world.

Thanks Brent.

I’ve heard the whisper, and hope to search out where I belong. I thought it was with my Pickleball community, but that wasn’t it… I’m thankful that I heard the whisper loudly while working, which led to my retirement. I believe it comes down to your simple comment on “The less I want to work for money.” Thanks for sharing your story, so that the rest of us have hope, and focus on the simplicity that God provides for us.