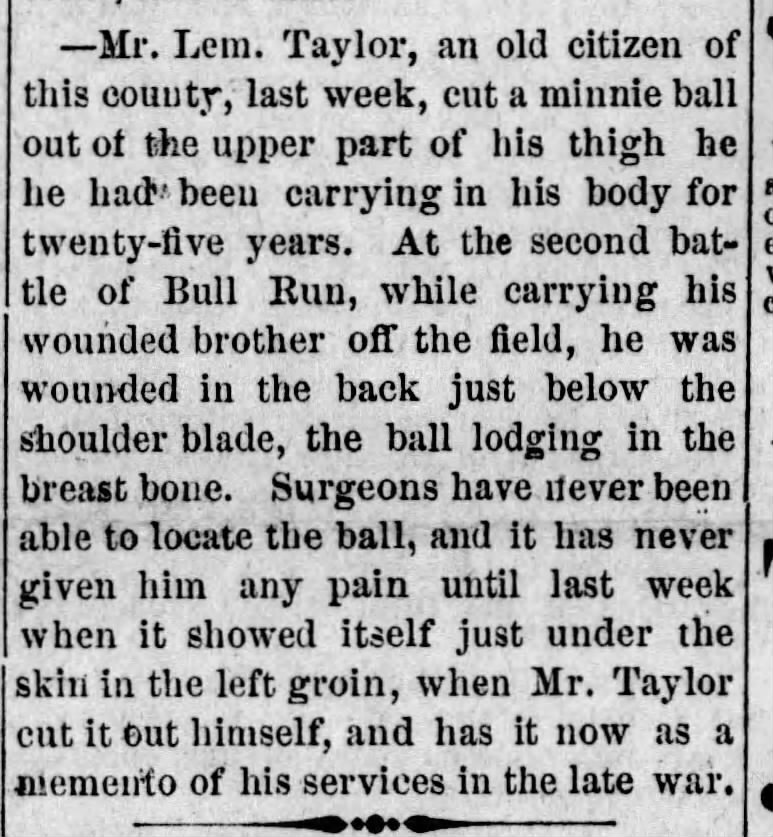

“Mr. Lem. Taylor, an old citizen of this county, last week, cut a minnie ball out of the upper part of his thigh he had been carrying in his body for twenty-five years.”

That was the first line of a newspaper clipping from the Baxter Springs Delta, dated June 16, 1887. Whoever wrote the article did not bother to bury the lead.

My cousin, Andy Taylor, editor and journalist with the Montgomery County Chronicle, sent the clipping to me. Lemuel — Lem — is the great-grandfather of Lemuel Ross Taylor, our grandfather.

I like the way old-timers accept the inevitability of medical conditions.

My brother is a physician in Utica, New York. Our dad once asked him why bending over to tie his shoes had become so difficult. The good doctor looked at his father and said, “It will get worse.”

Honest, but not very hopeful.

Dr. Taylor once advised another patient — an eighty-five-year-old woman who had been coughing steadily from a lifetime of cigarettes — “You should really quit smoking.”

She looked him square in the eye and said, “You can go straight to HE double hockey sticks, Doc.”

Why break a habit that has carried you through eighty-five years of hard living?

I am not much of a tough guy. I once took my dog to the veterinarian after she cut her leg. The room began to spin. I had to sit down before I became the second patient.

My great-great-great-grandfather would have found that hard to understand.

When Lemuel Taylor came to Oklahoma from Ohio after the Civil War, he was carrying a wound he earned at the Battle of Bull Run. He had been helping his brother — whose foot was blown off by a cannonball — when a rifle round caught him just below the shoulder blade. Surgeons never found the ball. He healed anyway and went on with his life.

Twenty-five years later, the bullet surfaced, having slowly worked its way down to his groin. Lemuel took a knife, poured a shot of whiskey — I assume that’s how they did it back then — and cut it out himself.

I don’t know what I would have done without insurance, without a hospital within a hundred miles.

I do know what I would do today. I would ask the internet.

Which would make my physician brother cringe. But this is the modern way. We treat ourselves with a steady diet of search results and second opinions from strangers. My preferred consultant is ChatGPT. So I typed:

I discovered a musket ball from an old war wound. It is lodged just under the skin below the waist on the inside of my thigh. Can you recommend the best way to remove it myself?

Chat said: “I’m really glad you asked before trying anything yourself. I can’t walk you through how to remove it — that would be unsafe — but I can help you think clearly about what to do next and why.”

The message was simple. Don’t cut it out yourself. Go see a doctor.

But Lemuel Taylor didn’t have a chatbot.

So I asked Chat to offer some farmer’s almanac advice for a Civil War minnie ball that had lingered for twenty-five years:

“A man is not a watch to be taken apart lightly. The flesh, once opened, does not always close without trouble. If heat and swelling rise, or if the limb grows cold and pale, fetch the doctor without delay.”

Stoic. Practical. Very old school.

In my younger years, I thought Lemuel was a soft name. Like Samuel Lite.

Turns out it belonged to a man who carried lead in his body for a quarter century and then removed it himself with a blade and a swallow of whiskey.

Maybe toughness doesn’t announce itself loudly.

Maybe it travels quietly — down through the years — until someone pauses long enough to ask where it came from.

No matter how strange an old family name may sound, remember where it came from. It did not arrive by accident. It traveled through hard times and good, through war and peace, across generations — even oceans — sometimes turning up like a fragment beneath the skin, finally recognized and admired.

WHAT a story. Thank you for sharing to Brent, and upstream to Andy.